Diagnostic Imaging During Pregnancy and Lactation

/Today we’re going to review a source of constant consultation and confusion: diagnostic imaging during pregnancy and breastfeeding. ACOG CO 723 is the definitive reading on this subject, and we use it to structure this episode. Critical take home: ACOG states that critical imaging studies should not be withheld from a pregnant patient if needed to make a diagnosis.

Ultrasound

Sonography utilizes sound waves to produce a visible image, and is not a form of ionizing radiation.

Thus, it is considered the safest mode of imaging in pregnancy.

However, ACOG still recommends sticking to the ALARA principle of exposure in pregnancy (“As Low As Reasonably Achievable”) to minimize any potential untoward effects.

One of these theoretical effects involves color or spectral flow Doppler. Due to its intensity, the theoretical temperature increase surrounding the area being study can be as high as 2deg C, or 3.6deg F. It’s unlikely than any temperature increase would be sustained at any fetal anatomic site to cause harm. However, for this reason, even ultrasound exposure should be used judiciously.

MRI

Allows for visualization of soft-tissue structures like ultrasound

However, as MRI is operator-independent, pick up rates for certain pathologies like appendicitis tend to be higher.

There are no special contraindications or considerations in pregnancy for non-contrast MRI, other than the usual screening surrounding metal or magnet-sensitive implants, such as pacemakers.

Non-contrast MRI is sufficient for diagnosis; however, some diagnoses or studies may be improved by the use of gadolinium-based contrast, for which there is uncertainty regarding fetal effects.

Gadolinium is water-soluble, and thus crosses the placenta into fetal circulation.

Free gadolinium is toxic, so it is bound, or chelated, when administered for studies.

There is concern that since this bound gadolinium can enter fetal circulation, it can recycle in the fetal circulation. This potentially could sit for long enough that the gadolinium could dissociate and become free; thus become toxic.

Given at least the concern for potential poor outcomes, gadolinium-based contrast should be limited in use to cases where there is an absolute clear benefit to its administration.

Gadolinium’s water-solubility makes it an OK contrast agent to use during lactation.

Less than 0.04% of a dose of gadolinium will be excreted in breastmilk in the first 24 hours, and less than 1% of this will be absorbed in the infant GI tract. Thus, breastfeeding should not be interrupted after gadolinium contrast studies.

CT, XRAY, and other ionizing radiation studies

Before talking about ionizing radiation studies, it’s important to know some vocabulary and measurements of radiation:

Exposure is the number of ions produced by radiation in the form of X-rays or gamma rays per kilogram of air. This is measured in Roentgen units.

Dose is the amount of energy deposited per kilogram of tissue. This is the usual consideration when we talk about radiation in pregnancy. This is measured in rads or in Gray units; 100 rad is equivalent to 1 Gray.

Relative effective dose is the amount of energy deposited per kilogram of tissue, and normalized for biological effectiveness on the tissue. This is measured in Roentgen equivalent men (rem) or Sievert units.

Again, the dose is what we usually consider and track with respect to radiation in pregnancy.

The background dose of radiation a fetus is exposed to during pregnancy is around 1 mGy.

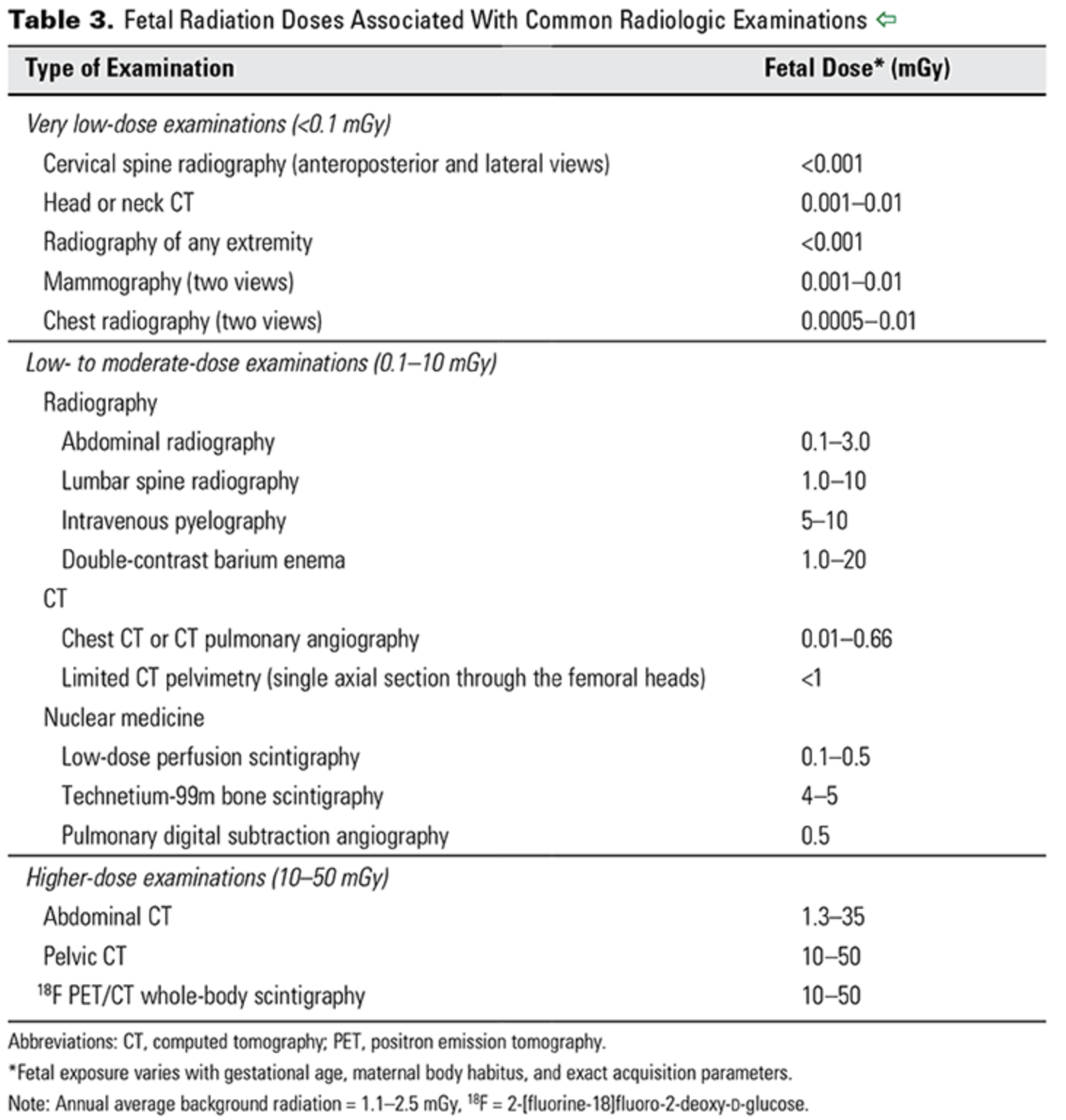

From CO 723 — a reference for doses associated with different imaging studies.

ACOG CO 723

The risk of radiation exposure on a developing fetus depends on both the dose of radiation, as well as the gestational age at which the exposure occurs.

For instance, if an exposure of 50-100 mGy occurs prior to implantation (0-2 weeks post fertilization), there is generally an all or none effect; that is to say, this usually results in miscarriage, or no consequence at all.

During organogenesis, or 2-8 weeks post-fertilization, congenital anomalies or growth restriction can be seen with cumulative doses of 200-250 mGy.

The risk of severe intellectual deficit or microcephaly is most prominent around 8-15 weeks, with doses between 60 - 300 mGy.

There is an estimated 25 point IQ loss per 1000 mGy exposure during this time period.

A lower risk of severe intellectual disability may persist through 25 weeks gestation, though again with exposures of 250mGy or more.

Other risks include childhood cancer. With respect to leukemia, it is estimated the risk of childhood leukemia increases 1.5-2 fold with a 10-20mGy dose, over a background leukemia risk of 1 in 3000.

Radiologists and radiation physicists can help to calculate doses for patients exposed to multiple studies or with occupational hazards.

With respect to contrast:

Oral contrast poses no real or theoretical harm to pregnant or lactating mothers and their infants.

IV contrast tends to be iodinated, but is also water-soluble.

So similarly to gadolinium, in pregnant patients this crosses the placenta.

Animal studies have demonstrated no teratogenic effects from its use, but it is recommended to limit use of iodinated contrast unless necessary.

Also similarly to gadolinium, because of this water solubility, iodinated contrast is excreted minimally in breastmilk, and breastfeeding should be continued without interruption.

Nuclear medicine studies

Radioisotopes for nuclear medicine studies, such as VQ scans, thyroid scans, and bone scans, are variable in their potential effects on the fetus.

Technetium-99 is one of the most common radioisotopes used for these studies, and given its short half life of 6 hours as well as its pure gamma ray emission, is generally accepted as safe to use when indicated in pregnancy.

Radioactive iodine (I-131), by contrast (punny!), readily crosses the placenta and has a half-life of 8 days, and has known adverse effects on the fetal thyroid. Thus, it is contraindicated for use in pregnancy, and is also recommended against use in breastfeeding mothers until breast milk has been cleared of the radioisotope.