Surgical Injury Part II: Ureters and Bowels

/Bowel Injuries - Enterotomies and Colotomies

Tips for Prevention

Surgical technique is crucial in preventing bowel injury.

Adhesions can hide the bowel quite well!

Entering peritoneum – bowel loop adhered to anterior abdominal wall – very common scenario for injury.

Endometriosis – leads to scarring and adhesions, or bowel may be directly impacted and injury may occur with excision.

When breaking down adhesions:

Gentle, controlled traction and countertraction on bowel loops.

Sharp, cold dissection is preferred – typically Metzenbaum scissors or scalpel.

Blunt dissection may cause the bowel to tear.

Gentle, blunt dissection may be useful for some translucent adhesions – rub your thumb and index finger back and forth over the tissue to loosen it up, then switch back to sharp dissection once the adhesion “window” can be seen.

This can be a long process in some surgeries! Patience is key. Don’t be afraid to move to another area if you’re not making progress in one spot.

“Running the Bowel”

You’ve probably heard of this before… but how do you do it, exactly?

Most of the time, we’re talking about small intestine:

Start at the Ligament of Treitz.

This band of tissue extends from the diaphragm to the duodenojejunal flexure - so up high (close to T12) and posteriorly (remember the duodenum is largely retroperitoneal).

Hand over hand, move down the bowel, inspecting for injury or perforation.

You’ll start in the jejunum, and move to the ileum of small intestine.

There’s no landmark to distinguish these two, but the ileum feels thinner and the lumen is somewhat smaller.

For small intestine, you end your run at the ileocolic junction.

This is denoted by the appendix!

Large intestine is distinguished by epiploic appendages, outpouchings of the colonic wall (haustrae), and three large muscular bands (taenia coli).

Should also be inspected for injury if suspected!

Site and extent of injury

Technique

Critically important – repair to bowel injuries are done perpendicular to the long axis of the bowel.

I.e., if you are looking at bowel in your hand going right-to-left, your repair is up-and-down.

If you repair parallel to the long axis of the bowel, the bowel lumen will narrow and potentially cause obstruction.

Operative obstetrics and gynecology - Correct technique for bowel repair

Serosal injuries:

If underlying muscle and mucosa are intact and the serosal injury is small, then this can be left unrepaired – stitching may just increase complications.

If muscle is torn as well, then repair should be performed as the muscle provides integrity – the bowel wall may perforate without overlying muscle.

Small, tapered needle with 3-0 or 4-0 silk.

Avoid placing the stitch through the mucosa and into bowel lumen!

Perforating injuries:

Ideally they are repaired immediately to limit contamination of the peritoneal cavity!

Antibiotics should be given to cover anaerobic intestinal flora, if they haven’t already:

Typically a dose of metronidazole

Smaller perforations can typically be closed in a two-layer fashion:

Inner layer of absorbable, braided suture (i.e., 3-0 Vicryl or Polysorb) that goes through the full thickness of the bowel.

Need to ensure mucosal approximation for a water tight seal!

Outer layer is the seromuscular repair as we described before, with 3-0 or 4-0 silk.

Larger perforations may require bowel resection and reanastamsois.

Should be considered if perforation:

Involves more than 50% of bowel wall circumference

There are multiple perforations within a short segment of bowel

There is vascular compromise to a segment of bowel

If you see the serosa appears dark and dusky and fails to pink up after a few minutes… likely needs resection.

This is generally beyond the skillset of a generalist OB/GYN - so call your general surgery or colorectal surgery friends to help with these.

Regardless of size, irrigation should be performed copiously to clear out intestinal spillage, particularly if there was a colotomy.

Surgery may advise placement of a Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain with spillage occurring, to monitor for leaks at site of bowel reanastamosis – this is less and less common as better evidence has emerged that drains don’t alter outcomes.

We are definitely not the experts here – defer to surgical colleagues on indications and necessity of drains!

Management after Injury/Repair

Timing of feeding after bowel injury and repair is also controversial.

However, most recent evidence in colorectal surgery suggests that early enteral (PO) feeding is feasible and safe, with early frequently defined as within 24 hours of surgery.

Small injuries that are within the purview of OB/GYNs to repair do not need to have feeding restrictions.

Larger injuries where you’re obtaining consultation for sure – defer to your surgical colleagues.

Ongoing antibiotic therapy and postoperative imaging studies are generally not warranted.

Ureteral Injuries

Prevention

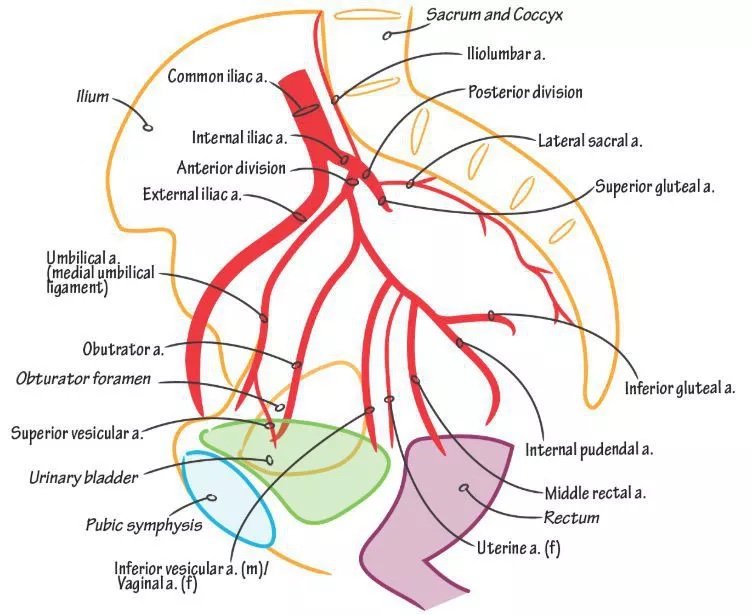

Knowing your anatomy is really important, as the ureter runs in some high-risk areas:

At the pelvic brim, where it crosses the bifurcation of the common iliac artery – injury can occur with hypogastric artery ligation.

In the pelvis, just below the infundibulopelvic ligament – can be injured with oophorectomy.

Beneath the uterine artery – often coursing laterally within 1.5 - 2cm – site of injury often in cesarean, if it occurs, and of course at hysterectomy.

From there it courses medially and ventrally, around the cardinal ligaments to enter the trigone – also a high risk point of injury at hysterectomy, as well as in urogynecologic surgeries like anterior colporrhaphy and uterosacral ligament suspension.

Risk goes up with more complex surgeries – be particularly aware with:

Malignancy

Large fibroids

Adhesive disease and PID

Placenta accreta and cesarean hysterectomy generally

Vaginal hysterectomy with significant prolapse

Congenital anomalies

Do preoperative stents help?

They may be helpful for identification of ureters and dissecting around them, however, there’s no evidence to say they reduce the risk of injury.

They may help you identify it once it happened, though!

Consider them on a case-by-case basis with high risk procedures.

Detection

Intraoperative detection is so much better than delayed injury.

Injuries can cause transection which is easily detected, but also be aware that injuries may be delayed particularly with thermal injury, crush injuries, or overly aggressive dissection leading to devascularization.

Dye solutions (indigo carmine, methylene blue, fluorescein) provided intraoperatively can allow you to see:

Extravasation of dye in the surgical field – an abdominal transection injury

Failure to see ureteral efflux on cystoscopy – more likely a crush injury, or a kink from a suture.

Cystoscopy is very helpful:

You want to see brisk efflux – wisps of dye passage may suggest partial occlusion or kinking.

Stents can be passed if you’re qualified, or by urologic consult.

If stents pass easily and dyed urine drips from a stent, it’s likely that ureter of concern is kinked somewhere – review, release suture, and cystoscope again to see if that causes improvement.

If stents cannot pass more than a few centimeters, ligation or transection likely occurred.

Dye can be passed through a stent retrograde as well to aid in visualization in the abdomen of an injury site.

Unfortunately, 50-70% of ureteral injuries are not diagnosed in the acute setting.

Delayed recognition of injury manifests as flank / abdominal pain, anuria, urinary ascites, and concern of course for fistula development (copious discharge from wound and/or vagina).

If suspected postop, workup is usually through CT scan (IV pyelogram - preferred) or a retrograde pyelogram.

Repair techniques (a brief review, as if an injury occurs this will be done by consultant, typically):

Depends largely on the site and mechanism of injury.

Stents: may be needed alone for some crush injuries or other ‘minor’ damage.

Some small laceration injuries (<50% diameter of the ureter) can be primarily sewn over a stent.

If over 50%, requires anastomosis or reimplantation.

Ureteroneocystotomy: the ureter is reimplanted into a deliberate cystotomy site.

Typically for distal injuries.

Modifications if additional mobilization is needed include:

Elongation of the bladder

Psoas hitch: a technique where the bladder is hitched up onto the psoas muscle to bring it closer to the ureter.

Ureteroureterostomy: can be:

Ipsilateral – the two cut ends are brought back together. Most common.

Transureteroureterostomy (contralateral) - essentially connecting the ureter to the other side, creating a “Y-shaped” drainage. For more complex repairs that are more proximal. Not common.

Boari flap: similar in principle to a psoas hitch, but a lot more extensive – the bladder is essentially turned into a tube to allow for greater reach for more proximal injuries.

Postoperative management:

Guided by urology – stent needs to be left in place for healing for a while, usually 2-6 weeks.

If cystotomy as well, a Foley catheter would also be left.

Retrograde pyelogram can be performed at time of stent removal to demonstrate healed tissue without leaking or stenosis, and patients should be followed by urology postoperatively.