TORCH Infections

/Today we do a mega-episode on TORCH! There’s lots to cover here, so we’ve put everything into a mega table format.

(C) CREOGs Over Coffee (2019)

Today we do a mega-episode on TORCH! There’s lots to cover here, so we’ve put everything into a mega table format.

(C) CREOGs Over Coffee (2019)

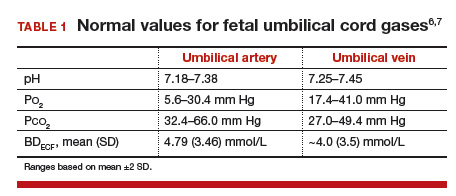

Building somewhat on our fetal circulation episode from last week, today we’ll talk about umbilical cord gases. From an obstetrics perspective, these can be challenging to really interpret, but the simple interpretation is often worth some CREOG points if you can analyze these systematically.

Remember, the umbilical vein is carrying oxygenated blood, and the umbilical arteries are carrying deoxygenated blood. This can help you remember the normal values, as they’ll be opposite those for an ABG versus VBG on an adult. Additionally, the umbilical vein is originating at the site of the placental interface with the mother -- so venous pHs will give a sense of maternal acid-base status, or the acid-base status at this interface. For this reason, the arterial pH is more helpful to truly measure fetal acid-base status.

The components of the blood gas are:

pH: represents the inverse log of the concentration of hydrogen ions in the circulating blood, or how acidic the blood is. In essence, more acid represents a lower pH, which represents more compromise.

Normal value for a venous pH is around 7.35 (as it is in adult blood).

Normal value for an arterial pH is around 7.28.

pO2: the pressure of oxygen (in essence its concentration) in fetal blood.

pCO2: similarly, the pressure/concentration of CO2 in fetal blood.

The pO2 and pCO2 can given additional clues to help with non-straightforward (i.e., mixed) acidosis.

Base Excess/Deficit: in blood, acid is buffered by bicarbonate ions. The base excess or deficit represents how much difference there is between those bicarbonate ions and hydrogen ions in order to return to a normal pH value of 7.35 in the umbilical vein. An excess is more bicarb; a deficit is less bicarb. However, these tend to get used interchangeably, and in these acid-base status questions, you’ll see the “excess” written as a negative number — implying what is actually a deficit.

Normal values for base excess are around 4 mmol/L in both the umbilical artery and vein.

A more significant base deficit signifies a metabolic acidosis -- i.e., the process causing insult has been longstanding, and there has been time to utilize bicarbonate to buffer the acid.

A lower base deficit signifies a respiratory acidosis -- i.e., the process has been acute, so there has been no buffering of the hydrogen ions.

A base deficit of 12 mmol/L has been suggested as severe, and more suggestive of metabolic acidosis.

(c) MDEdge

What about administering more O2 to the mother? Won’t that help things and reduce the fetal risk of acidosis?

If only it were that simple! Sadly, the answer is no. In most cases, maternal hemoglobin is fully saturated on room air. Fetal hemoglobin has a greater O2 avidity, and will pull O2 across the placental circulation. But when maternal blood is already saturated, the fetus won’t get any more O2 even if you pump it up to 4000L a minute by mega face mask! Some studies have suggested the additional free O2 in maternal serum may actually lead to vasospasm and cause harm!

The exception to this certainly is a change in maternal oxygenation or an indication for maternal O2 use -- but these indications suggest that maternal Hb is less than 100% saturated.

When should I get a cord gas?

It’s a good idea to practice the technique for cord gas collection, which requires collecting a 10-20cm doubly-clamped (i.e., proximally and distally) cord segment. Even on routine, vigorous deliveries, getting into this habit as part of your deliveries will help you be prepared.

Cord gases are not recommended to be sent with delayed cord clamping, so don’t send these if DCC is part of your practice! However, collecting the cord segment can be good practice for those learning proper technique.

There are no consensus rules about when to send a cord gas sample. At our institution, the general thought is “if you think you need one, send one.” However, common scenarios where cord gas sampling can be helpful to at least set aside on a “just in case basis” include:

Nonvigorous infant at delivery (i.e., Apgars at 5 mins less than 7)

Category III or “bad category II” tracings

Operative deliveries performed for NRFHT

Multiple gestation

Premature infants

Meconium stained fluid

Growth restriction

Breech deliveries

Shoulder dystocia

Intrapartum fevers or chorioamnionitis

Obviously this list is non-exhaustive, but goes to show there are a lot of indications! Some literature has suggested even universal arterial blood sampling at delivery may be cost-effective.

The best way to learn this is to do some practice cases. Check out the below resources for some practice questions and further explanations.

Today we tackle a topic recent to us — application season. While it’s fresh in our heads, we’ll be interviewing folks from around OB-GYN to get their input on subspecialty applications, as well as job interviews for the OB-GYN generalist, so stay tuned!

Admittedly we come from an academic institution, so we try our best to generalize information to be relevant to all; however, keep in mind your exact environment/context while listening. And if you have your own tips to share, please write to us!

The highlights:

PGY I & II

Determine that you want to do MFM!

Think about some research ideas, and get started if you can.

Identify mentors - near or far.

Go to SMFM!

Do well on your CREOGs!

PGY III

Continue your research projects, talk about your interests with your mentors.

Start identifying people that can write your letter of recommendation.

Apply for the Quilligan Scholars Program (Due date: October 1)

Sponsored by the Foundation of Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine, this award identifies early leaders in MFM in third year residents. There are approximately 8 scholars a year. The Foundation pairs honorees with leaders in the field and sponsors you to go to SMFM annual meeting - an excellent opportunity!

Middle of the year, around January:

Start looking into programs that you may be interested in applying to

Sit down with your mentors and come up with a list of how many programs to realistically apply to; try to get between 10-12 interviews.

Identify with your mentors what you’re really looking for in your MFM career - do you want to be clinical? Be academic? Be a grant-funded researcher? Go into private practice? The field is huge and different, and there will be a right program for you!

Application Season:

PGYIII, Feb/March:

Go to SMFM - maybe present if you can. Get a sense for the programs at the meeting. Additionally, you can use the SMFM website for resource to fine-tune your list.

Write your application - get ready to go down memory lane with ERAS!

Write your personal statement, and make it personal!

Submit your applications by May 1 - this is really when programs start to actually look at applications.

Interviews

May-June: receive interviews and schedule interviews.

June - September: go on interviews. Things to know:

Professional dress and appearance.

It’s expensive - budget appropriately!

Ask the fellows what their day-to-day schedule is like. Really know what you want and ask about it. Whether that’s the research, the job placements for fellows post-fellowship, or something that’s unique to you, programs should be able to give you a sense of whether they focus on your interests.

Do they feel like your people? Sometimes it’s just a gut feel!

Rank Lists

Be sure to reach out to those that you liked. Tell your #1 program that they’re your #1!

You can write thank you notes… or not. Some programs just won’t talk to you no matter what after the interview, and that’s OK.

Ask your mentors to reach out for you, particularly at your top choice(s).

One of the neonatology/pediatric points the CREOG exam will test on is flow of blood through the fetal circulation. It can be quite confusing, but it’s worth remembering. We’ll take you on the journey of a red blood cell in today’s episode.

The important foundational bit of knowledge for this is the nomenclature of arteries and veins. Arteries carry blood away from the heart (Arteries Away), whereas veins carry blood towards the heart. Arteries and veins do not denote oxygenation status, particularly in the fetal circulation!

(C) Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Let’s start at the umbilical vein, which is carrying oxygenated blood from the placenta towards the fetal heart. Remember there is a single large umbilical vein with normal umbilical cords.

The umbilical vein enters at the umbilicus, and moves superiorly towards the liver, where it ultimately needs to meet the inferior vena cava. However, the umbilical vein naturally empties into the portal hepatic vein.

This is where we encounter our first fetal shunt, the ductus venosus.

This allows oxygenated blood from the umbilical vein to connect to the inferior vena cava, bypassing the portal vein and the liver.

The ductus venosus closes functionally in term infants within minutes of birth, and full closure naturally occurs within one week of birth. In preterm infants this may take longer. The remnant structure is known as the ligamentum venosum.

From the IVC, we can get blood into the right atrium of the heart. Now blood will move to the right ventricle naturally in adult circulation. In fetal circulation, though, the lungs have yet to open. The pulmonary circulation is of very high resistance. Rather than take the long, high resistance trip around the lungs, we encounter our second shunt, the foramen ovale between the right and left atria.

The relatively high pressure in the right atrium allows for blood to move across this shunt into the left atrium.

With the first neonatal breaths, the lungs open and the resistance to the pulmonary circulation drastically drops. This allows for the foramen ovale to close, as the septum secundum (some tissue in the right atrium where the foramen ovale is located), is effectively a one way valve from right to left; when flow starts to go left-to-right, this valve closes.

In up to 25% of adults, this one-way valve closure is not completely effective, leading to the patent foramen ovale.

Now blood is in the left heart, where it can move from left atria, to left ventricle, to aorta, and now supply the fetal brain and other tissues.

However, some blood may still move to the right ventricle in spite of the pressure gradient, and try to move through the pulmonary circulation.

To exit the pulmonary circulation more quickly and supply oxygenated blood to the lower extremities, we encounter our third shunt, the ductus arteriosus. This connects the pulmonary artery to the descending aorta. After birth, this closes and becomes the ligamentum arteriosum.

In some individuals, the ductus arteriosus remains open, leading to a patent ductus arteriosus. Because of the change in pressure after birth, now oxygenated blood is leaving the aorta and overloading the pulmonary artery. This can lead to pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure.

In PDA and rarely PFO, but more commonly with ventricular septums, the pulmonary hypertension becomes so great as to change the pressure differential again (i.e., pulmonary or right heart circulation pressure is greater than left heart or systemic circulation). This changes the shunt to send deoxygenated blood from the right heart into the systemic circulation, and is known as Eisenmeger syndrome.

Now that we’ve gotten all the blood to the left heart, it moves through the arteries to supply organs and tissues, and will end up in the veins.

Coming from superiorly, blood will end up in the superior vena cava, and end up back in the right atrium. From here, it’s the same cycle all over again -- some will go through the foramen ovale, some will go to the right ventricle and pass through the ductus arteriosus.

If blood went inferiorly (i.e., went through the descending aorta/ductus arteriosus), the umbilical arteries will carry blood back towards the placenta for re-oxygenation and deposition of CO2 and waste products.

The umbilical arteries originate off the internal iliac arteries bilaterally. After birth, they become obliterated and are known as the medial umbilical ligaments. These can be seen during laparoscopic surgery and are good markers for the position of the superior vesical arteries. More on that in a future episode on pelvic anatomy!

Though we have the anatomic picture above, some folks may find a schematic helpful. Run through this a few times before your exam and you’ll be golden!

(C) Epomedicine

Shout out to Taylor DeGiulio for today’s episode idea! We’re doing a pretty close reading of ACOG PB 195 if you want to follow along!

SSI represents the most common complication after GYN surgery, however definitions of this may surprise you. The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) divides SSI up into three broad categories, with their definitions below:

Superficial incisional: occurs within 30 days of surgery, involving only skin or subcutaneous tissue.

Deep incisional: occurs within 30 days of surgery without an implant, or within 1 year of surgery with an implant, and involves deep soft tissues (rectus muscle, fascia).

Organ space: occurs within 30 days of surgery without an implant, or within 1 year of surgery with an implant, and involves any other area manipulated during operative procedure (i.e., osteomyelitis if bone, endometritis or vaginal cuff for GYN, etc.)

In addition to satisfying these time and location definitions, an SSI also must have one of the following characteristics present:

Purulent drainage from the area of infection.

Spontaneous dehiscence or deliberate opening of a wound by the surgeon, with organisms subsequently obtained from an aseptically collected culture; or not cultured, but the patient displays signs/symptoms) of infection (i.e., fever, localized pain or tenderness, redness, etc.).

Abscess or other evidence of infection noted on examination.

Diagnosis of infection made by surgeon or attending physician.

In GYN surgery, our threats for infection lie primarily from vaginal organisms or skin organisms; however we may also come into contact with fecal content or enteric contents as well. Thinking about the organisms we’re helping to bolster defense against will help in selecting a preventive antibiotic. Thinking about the wound class is a simple way to characterize this:

ACOG PB 195

ACOG also recommends a number of perioperative considerations/techniques to reduce SSI:

Treat remote infections - this one seems pretty obvious. If there’s an infection going on, like a skin infection or a UTI, it’s likely best to postpone surgery in favor of treating the infection!

Do not shave the incision site - Preoperative shaving by patients themselves has actually been shown to be likely harmful, increasing the risk of infection by introducing a nidus for infection remote from surgery. If hair needs to be clipped, it should be done immediately pre-op with electric clippers.

Prevent preop hyperglycemia - blood glucose should be targeted to < 200 mg/dL for both non-diabetic and diabetic patients before proceeding with surgery. Performing a preoperative random blood sugar prior to major surgery is a practice our hospital has implemented to identify diabetes in our patients, and to prevent SSI.

Advise patients to shower or bathe with full body soap on at least the night before surgery -We found it fairly surprising that no particular soap is recommended over another. Many offices offer patients a chlorhexidine soap for use the night before surgery. The soap significantly reduces risk of cellulitis versus no bathing.

Use alcohol-based preop skin prep, unless contraindicated - chlorhexidine-alcohol combinations have been proven in RCTs and meta-analyses to be superior to povidine-iodine for preoperative skin preparation. For mucosal sites such as the vagina, where high alcohol concentrations should not be used due to irritation risk, povidine-iodine or chlorexidine soap solutions should be used.

Maintain appropriate aseptic technique - Of course, right? But in addition, our surgical technique does matter! Effective hemostasis while preserving vital blood supply, maintaining normothermia and reducing operative time, gentle tissue handling, avoiding inadvertent injuries, using drains when appropriate, and eradicating dead space can all help to reduce risk of SSI.

Minimize OR traffic - safety bundles that have included components to reduce opening of OR doors during cases have been shown to reduce SSI.

For hysterectomy, consider preop screening for bacterial vaginosis - prior to routine use of antibiotic prophylaxis for hysterectomy, use of metronidazole pre-op in patients who screened positive for BV reduced SSI. These studies haven’t been repeated with systematic antibiotic prophylaxis, but given the data, ACOG does state that screening is reasonable at the preop visit.

Alright, now time for the antibiotics! We dive deeper in the podcast, but PB 195 will give you the quick version here in the tables:

ACOG PB 195

ACOG PB 195

Twitter: @creogsovercoff1

Facebook: @creogsovercoffee

Support us at Patreon for shout outs, swag, and exclusive features!

Check out our friends at the OBG Project; residents, get OBGFirst for free via the Resident CORE curriculum!

Powered by Squarespace.

All content copyright CREOGs Over Coffee (2018 - present).

The views expressed herein represent those of the podcast authors personally, not of their institutions.

The podcast should not be reviewed or construed as medical advice.