Breast Imaging and Density

/Today we welcome Dr. David Edmonson, assistant professor in surgery and obstetrics and gynecology at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. Dr. Edmonson is an expert in breast disease and a surgical oncologist. Today he talks with us on imaging and breast density.

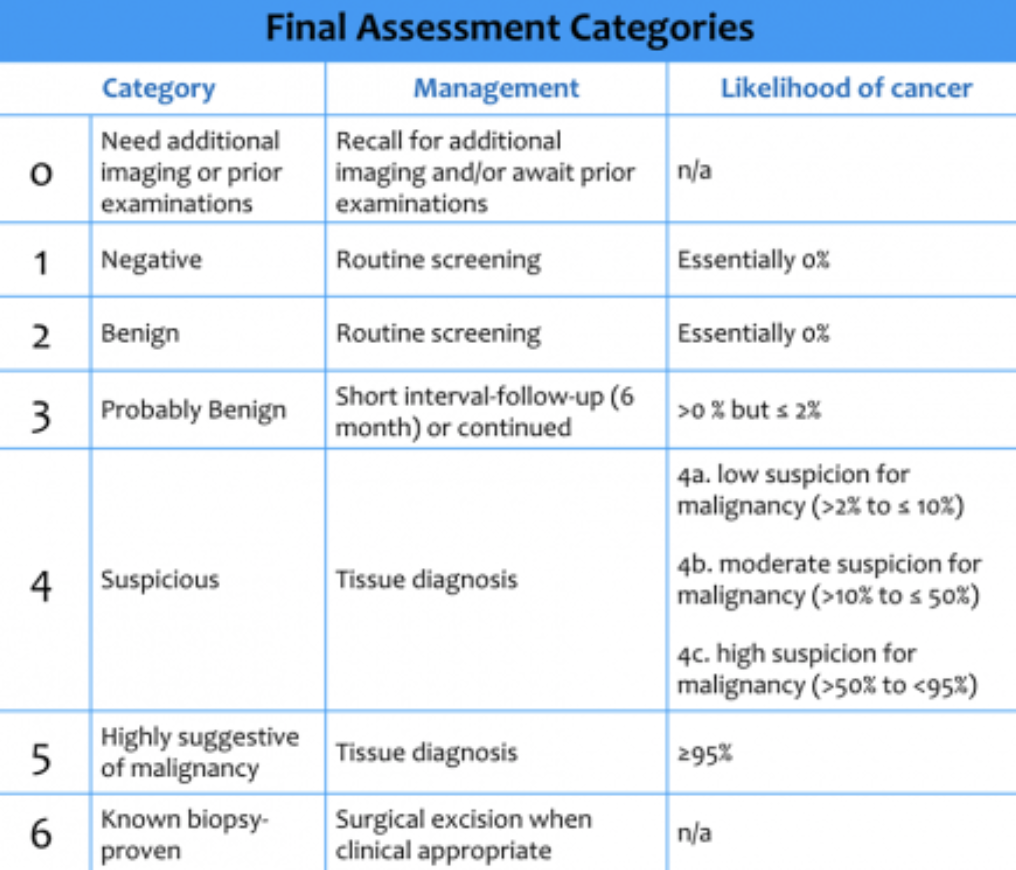

Mammography results can be classified into the BI-RADS (“Breast Imaging Reporting And Data System”) categories — it’s worthwhile to remember these categories and what the likelihood of malignancy is:

(c) Radiology Assistant

Mammography will also often report breast density. Breast density can hinder the utility of mammography, and depending on your area of practice, may suggest or require additional study. Dr. Edmonson does note that breast density requirements do have limited data, but are the subject of active study.

You can use risk models to help assess need for additional imaging: the Tyrer Cuzick or Gail models can be utilized, taking into account different risk factors.

To find out more about breast imaging and density, check out the immensely helpful DenseBreast-Info.org. On their website, there are multiple opportunities to expand your knowledge, including the CME opportunity Breast Density: Why It Matters as well as an FAQ for healthcare providers.